We have just looked at an approach to wireless power transfer using low MHz electromagnetic field oscillations. But such a concept is only “power transfer” if the whole reason for the signal in the first place is to transfer power. If such a signal exists for some other reason – like communications – then doing the exact same thing wouldn’t be power transfer: It would be energy harvesting.

And indeed folks are trying to harvest energy out of all of the waves running rampant through our environment. The issue is efficiency, however, and you don’t really see a lot of practical discussion of this type of harvesting as being on its way to commercialization.

But there are some interesting things going on. And they involve “metamaterials” – artificial matter that can achieve characteristics – like a negative index of refraction or negative permittivity – that aren’t possible in nature. We took a look at some of these a couple years ago.

I have tended to think of metamaterials as the careful stacking and arranging of materials at the nano level; apparently that’s not always the case. Some folks at Duke University created a microwave energy harvester using a macro-sized metamaterial.

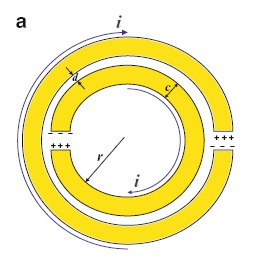

The fundamental unit of this “material” is the split-ring resonator. These can be very small, and would need to be on the order of 10s of nanometers across to respond to optical wavelengths, but the one Duke used was not that small: the outer diameter was 40 mm, and the gap was 1 mm. It was tuned for 900-MHz resonance.

Image courtesy ??(Wikipedia contributor)

My initial thought was that these were made out of a metamaterial, but no: they’re made out of copper, and an array of these becomes the resonator. They used five of them (5×1 array) in their experiments.

It’s interesting to me that one of these rings bears a remarkable resemblance to the structure that WiTricity uses as source and capture resonators, albeit at lower frequencies. I suspect that’s no accident.

While simulation suggested they might get into the 70% efficiency range, their results were closer to 37%. There wasn’t really an explanation of that discrepancy; I’m going to assume that will be the focus of more work.

You can read more details about their work in their paper (PDF).

Late update: there’s another “out of thin air” technology that’s more than harvesting. It will be the topic of a future piece…